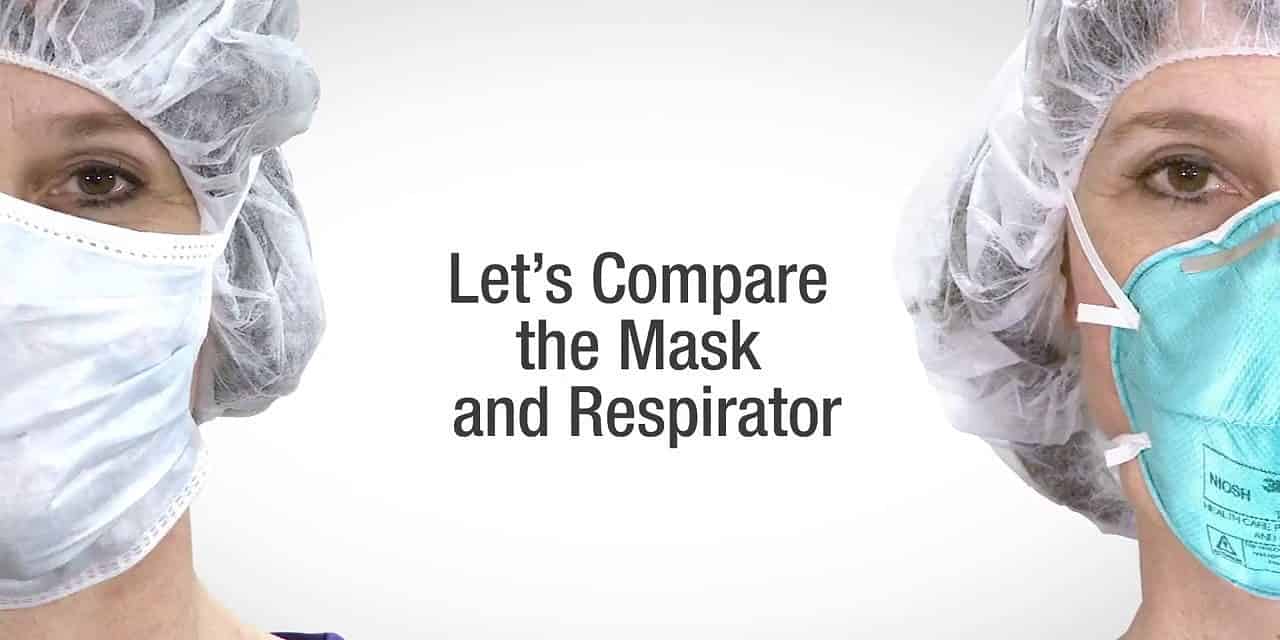

Background

Since certain disposable filtering facepiece particulate respirators are similar in appearance to many surgical/procedure

masks, their differences are not always well understood. However, respirators and surgical/procedure masks are very different

in intended use, fit against the face, wear time, testing and approval. The purpose of this document is to highlight some of

these differences, particularly for healthcare workers. Surgical/procedure masks may be provided to patients to help protect

healthcare workers and other patients from particles being introduced into the room as a patient talks, sneezes or coughs.

Wear Time

Respirators must be properly selected and carefully donned (put on) and doffed (taken off) in a clean area, and worn the entire

time in the contaminated area to have a significant effect on reducing exposure. Having the respirator off even 10% of the time

in a contaminated area significantly reduces the protective effect of the respirator.

Surgical/procedure masks are typically donned (put on) for a specific procedure. For infection control purposes, masks are

typically disposed of after each procedure/patient activity.

Testing

In the United States, respirators must meet test criteria stated in the Code of Federal Regulations 42 CFR Part 84. For a

complete understanding of all the test criteria, the reader will need to review the regulations. The filter efficiency test criteria,

which are employed by the U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), for respirators seeking

approval at the “N95” classification include:

• Sodium chloride test aerosol with a mass median aerodynamic diameter (MMAD) particle of about 0.3 μm;

• Airflow rate of 85 liters per minute (lpm);

• Charge-neutralized test aerosol; and

• Preconditioning at 85% relative humidity (RH) and 38ºC for 24 hours before testing.

Common tests for surgical/procedure masks include: particle filtration efficiency (PFE), bacterial filtration efficiency (BFE),

fluid resistance, differential pressure and flammability. Each test is briefly described below.

Particulate Filtration Efficiency (PFE)

The PFE test is a quality indicator for healthcare surgical/procedure masks. The PFE test is not an indicator of respirator

protection performance. The filter media of a surgical/procedure mask with a very high (>95%) PFE may nevertheless

be less than 70% efficient when tested with the NIOSH N95 test method. The results of the surgical/procedure mask

PFE testing and NIOSH filtration efficiency testing should not be compared. Conditions of the PFE test include:

• Polystyrene latex sphere test aerosol;

• Approximately 0.1 μm in size;

• Airflow rate of 28 liters per minute (lpm);

• Un-neutralized test aerosol; and No preconditioning.

Bacterial Filtration Efficiency (BFE)

This test assesses the ability of a surgical/procedure mask to provide a barrier to large particles expelled by the wearer.

It is not a substitute for a regulatory respirator filtration efficiency test and it does not evaluate the surgical/procedure

mask’s ability to provide respiratory protection to the wearer. The test method used to evaluate BFE is the American

Society of Testing and Materials (ASTM) method F2101-01.

Fluid Resistance

The fluid resistance test is typically conducted based on the ASTM Test Method F 1862, “Resistance to Penetration by

Synthetic Blood,” which determines the mask’s resistance to synthetic blood squirted at it under varying pressures.

Differential Pressure (Delta-P)

The Delta-P test is typically conducted based on the “Method 1 Military Specifications: Surgical Mask, disposable (June

12, 1975)”, MIL-M-36945C 4.4.1.1.1. Delta-P is the measured pressure drop across the surgical/procedure mask material

and is related to the mask’s breathability.

Flame Resistance

Surgical/procedure masks intended to be used in the operating room undergo testing to determine the flammability by

class. FDA recommends that Class 1 and Class 2 flammability materials be used. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration

(FDA) recommends the use of one of the standards below to test flammability.

• CPSC CS-191-53 Flammability Test Method (16 CFR 1610) Standard for Flammability of Clothing Textiles

• NFPA Standard 702-1980: Standard for Classification of Flammability of Wearing Apparel

• UL 2154

Conclusion

In conclusion, surgical/procedure masks are intended to help put a barrier between the wearer and the work environment or

sterile field. They may help keep spit and mucous generated by the wearer from reaching a patient or medical equipment.

They can also be used as a fluid barrier to help keep blood splatter from reaching the wearer’s mouth and nose. And, where

applicable, they are FDA cleared as medical devices and can therefore be used in surgery in the U.S.

However, surgical/procedure masks cannot provide certified respiratory protection unless they are also designed, tested, and

government-certified as a respirator. If a wearer wants to reduce inhalation of smaller, inhalable particles (those smaller than

100 microns), they need to obtain and properly use a government-certified respirator, such as a NIOSH-approved N95

filtering facepiece particulate respirator. If the wearer needs a combination surgical/procedure mask and a particulate

respirator, they should use a product that is both cleared by FDA as a surgical/procedure mask and tested and certified by

NIOSH as a particulate respirator. Such products are sometimes called a “surgical N95,” “medical respirator” or “health care

respirator.”

Respirator versus Surgical/Procedure Mask Decision Tree for Healthcare Workers

The following decision tree highlights potential considerations for the selection of respirators verses surgical/procedure

masks.

Figure 1:

Respirator versus Surgical/procedure Mask Decision Tree

*Here are some additional considerations to keep in mind when selecting a respirator for use in a healthcare work

environment.

• Selection of respiratory protection for occupational hazards is typically based upon the airborne concentration of the

substance that the wearer is exposed to and the occupational exposure limit (OEL) of that substance.

• Biological agents, such as viruses and bacteria, do not have OELs; therefore, employers should consider available guidance when selecting respirators. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recommended that

respirators offering more protection, such as powered air purifying respirators (PAPRs), may be considered in situations

when high exposures to bacteria and viruses are possible.

• The occupational use of respirators in the U.S. is regulated by the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration

(OSHA), and in the U.S., the use of respirators in all workplaces must be per OSHA standard 29 CFR 1910.134.

• Tight-fitting respirators such as disposable filtering facepiece particulate respirators cannot be worn with facial hair or

anything else that may interfere with the seal of the respirator to the wearer’s face.

1. In the U.S., surgical/procedure masks and surgical respirators must be cleared by the FDA for use in surgery. Surgical respirators must

be also approved by NIOSH. During times of respirator shortages, such as pandemics, CDC has recommended the use of unvalved

standard N95 respirators in combination with a fluid-resistant faceshield when surgical N95 respirators are not available.

2. In the U.S., particulate respirators must be approved by NIOSH.

3. ”Fluid resistance” refers to testing performed on surgical N95s per ASTM F1862, a standard test method for resistance of medical

facemasks to penetration by synthetic blood. This test is required because during certain medical procedures, a blood vessel may

occasionally be punctured, resulting in a high-velocity stream of blood.

4. Comfort masks are not designed to protect lungs from airborne hazards, are not NIOSH approved, and are not FDA cleared.

Resources

For more information regarding the differences between surgical/procedure masks and respirators, here are more resources:

1) Healthcare – Mask vs. Respirator Video -https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JR2uLfEVD2w

2) NIOSH science blog “N95 Respirators and Surgical Masks” Lisa Brosseau, ScD, and Roland Berry. October 14th,2009 https://blogs.cdc.gov/niosh-science-blog/2009/10/14/n95/

3) OSHA Fact Sheet: “Respiratory Infection Control: Respirators Verses SurgicalMasks”,https://www.osha.gov/Publications/respirators-vs-surgicalmasks-factsheet.html

4) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention “Understanding the Difference,”https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npptl/pdfs/UnderstandingDifference3-508.pdf

5) U.S. Food & Drug Administration: “Memorandum of Understanding Between the Food & Drug Administration/Centerfor Devices & Radiological Health and the Centers For Disease Control & Prevention/National Institute for OccupationalSafety & Health/National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory,”

https://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/PartnershipsCollaborations/MemorandaofUnderstandingMOUs/DomesticMOUs/ucm587122.htmPersonal Safety Division3M Center, Building 235-2W-70St. Paul, MN 55144-10003M PSD products are occupational use only.©3M2020.All rightsreserved. 3M isa trademark of 3MCompany andits affiliates. Usedunderlicense inCanada. Allother trademarks arepropertyoftheirrespectiveowners.Please recycle. In United States of AmericaTechnical Service: 1-800-243-46301-800-328-16671-800-267-44141-800-364-3577Customer Service:3M.com/workersafetyIn CanadaTechnical Service:Customer Service:3M.ca/Safety